conversations – Interview by Anika Meier – 03.01.2024

CHRIS COLEMAN AND DEV HARLAN IN CONVERSATION: "NATURE IS A CONSTRUCT"

NATURE AND TECHNOLOGY

Embark on a journey with Dev Harlan and Chris Coleman as they venture into the realms of 3D scanning and rendering. Ever wondered how real objects find their representation in the digital world or what happens when the ephemeral nature of digital media meets enduring physical artifacts?

In conversation with Anika Meier, artists Chris Coleman and Dev Harlan delve into the depths of their collaborative creation, THIN NATURES. In this insightful dialogue, they unravel the complex dynamics intertwining technology, nature, and human perception, providing significant perspectives on our digital realities.

Anika Meier: Chris, you are a Professor of Emergent Digital Practices and the Director of the Clinic for Open Source Arts at the University of Denver. What does teaching Emergent Digital Practices mean?

Chris Coleman: I've been teaching since 2001. The program we've developed at my university, Emergent Digital Practices, is an attempt to define creative spaces that are constantly emerging. Our classes change every six months. We're interested in a more fluid understanding of how creativity and technology come together.

We use the term Practices as opposed to emergent digital art because we embrace the full spectrum between when you're doing work for yourself and when you're doing work for a client, whether that work comes from internal or external spaces. We reject the notion that designers are different from artists, and they can't speak to each other because one of them sells out and the other one is poor. So we teach students to be creative across a full spectrum of activities. I bring stuff like 3D scanning and rendering into the classroom.

AM: When did you know that you wanted to be an artist?

CC: I studied mechanical engineering when I went to college. I was six credits short of a mechanical engineering degree. And I realized that my life was going to not have any creative output. So I quit school and went back to creating sculptures. I was raised to be creative; my whole life, I've been drawing, building, and sculpting. So it actually wasn't that much of a surprise to make this change to my life path. I just didn't allow myself to imagine becoming an artist professionally until I was in my mid-20s.

AM: And when did you start creating digital art?

CC: Back in 1997, when I started making art at the university, we didn't have a digital arts program. That was a new thing for a university to have, especially in a very poor state like West Virginia. I started out just doing sculpture. I was making tables, cedar chests, and strange metal sculptures. It wasn't until a couple of years into that period that I realized that I could leverage all of my digital experience from engineering and combine that with my sculpture practice. So I have a very intense craftsman background in the sculptural space, and I try to bring that intensity of craft to my digital work as well.

AM: Dev, when did you know that you wanted to be an artist?

Dev Harlan: How does one know what their path in life is? From an early age, as a teenager, I certainly had creative aspirations. I had originally been going to school for art; I learned painting and drawing. In the 1990s, I dropped out of art school to work in San Francisco during the dot-com boom. So early on, I was trying to make sense of that tension between an art career versus a design career and anxiety over whether I was "selling out" for expediency or money.

In San Francisco, I became embedded in the tech art and video art culture at the time, doing hardware hacking, video performance art, and all these other things that had no commercial applicability at all. I was forging my own path, but it was not entirely clear if what I was doing could be called art per se or if that was my intention or my goal. It wasn't until I came to New York and began to become more involved in the art community here that I got a better understanding of where I stood: between art and design. That's when I began developing a more serious physical practice with sculpture, casting, and modeling. I was using traditional materials, but combining those with the digital art practices that I had already developed while in San Francisco.

AM: Both of you have mentioned the commercial aspect of being an artist. How do you feel these days when it comes to selling art on the blockchain? As soon as an NFT is minted, it’s available on the market. Everyone can see what sells and for what price. Digital art has a price tag these days.

DH: I'll be very honest. It does feel very crass that everything immediately has a price tag on it. It does remind us what the base infrastructure of the NFT space really is, which is crypto. Being constantly reminded of that side can be distracting from the artwork.

That being said, these financial concerns still come up in the traditional art world when you're in a white-walled gallery in Chelsea with well-heeled people walking around, gazing at the art. It’s not just about appreciation of art for art's sake. There's commercial interest at stake. The traditional art world has developed ways of being perhaps more discreet about that side of the art world.

Having it out in the open does feel a little awkward and a little crass. Artists prefer to let other people deal with the transactional nature of being a working artist. The artist’s role is simply to be able to produce their work free from the constraints of the market. Increasingly, though, that's not really viable. In fact, there is a degree to which it is empowering for artists to be able to take control of the financial side of their career as well. There's pros and cons.

CC: I've been part of a couple hundred different exhibitions, festivals, and screenings over the last 20 years, and probably less than 1% of them have involved making my work available for sale. I'm not someone who has often participated in this aspect of the art market or the art world. That has meant missing some opportunities. There are parts of the art world that are deeply tied to this commercial space.

The last couple of years in particular have changed a lot of things, especially for collectors. My wife and I are not quite able to afford the work at some of the medium- and large-scale galleries that have traditionally existed. In the past, we relied on things like kickstarters, fundraisers, or sales directly from the artists. About a decade ago, things like s|editions and Daata Editions opened up new options, letting us collect more purely digital work. Now we're able to buy work in many different ways and in many different places. We've collected more work in the last three years than we could probably ever have collected in a lifetime before. So as a collector, this has been an exciting moment to see artists get to try many different things. We know that our money is going to support the artist directly.

AM: Chris, you’re a well-known collector on Tezos with an impressive collection. I enjoy looking through your collection from time to time to see whether I might have missed something on Tezos. Both of you have consistently released work on Tezos. THIN NATURES is your first release on Ethereum. I had invited both of you separately, and both of you immediately said yes. How did you start working on this exhibition together?

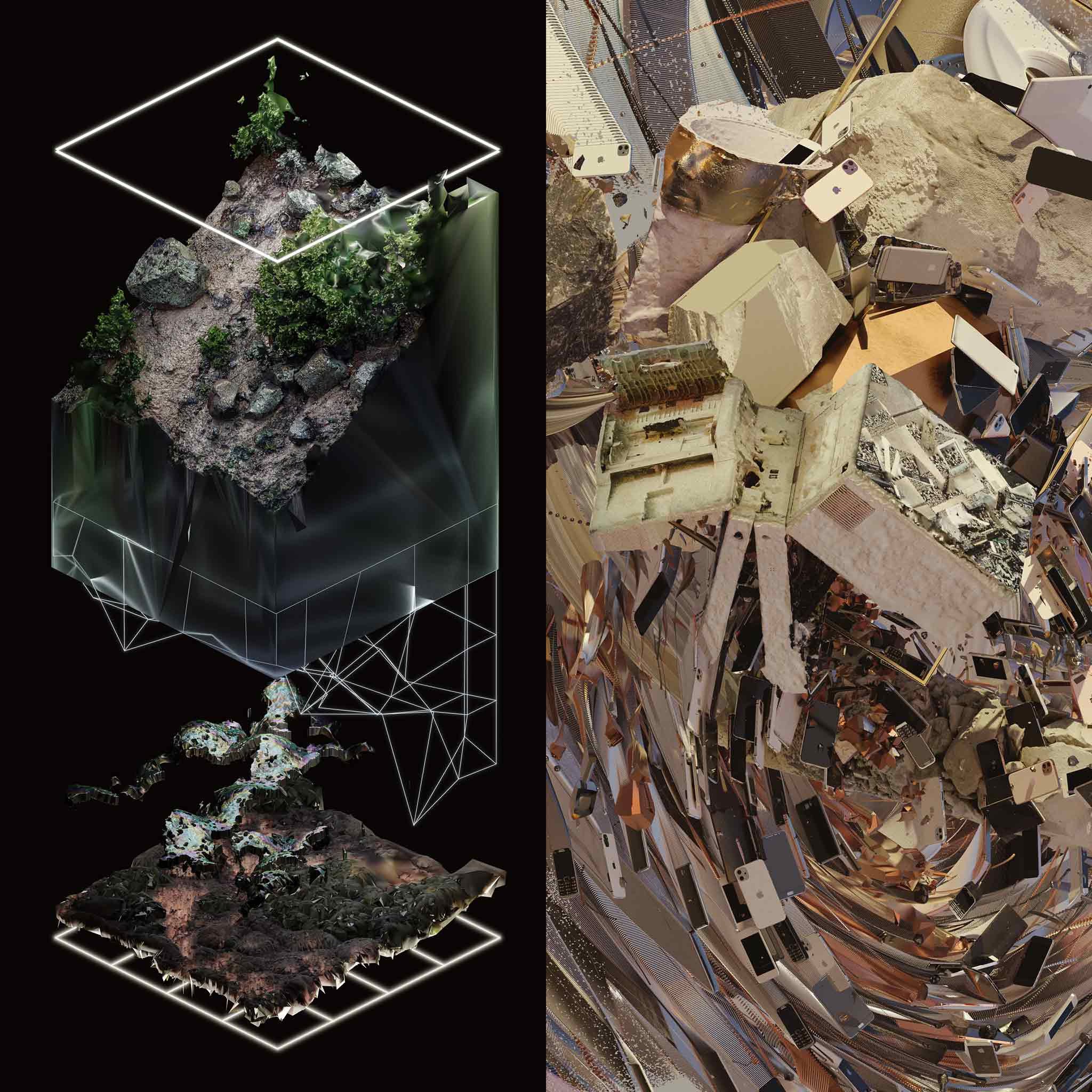

DH: It was easy for us to collaborate and make sense of each other's work. We're both working on very similar processes, but we're also working on very similar themes. It was not difficult to find a common ground for what we wanted the show to be about. After a couple of conversations, we were in agreement about the direction we wanted to go. Notably, there's no work in the show that is collaborative, but the concept of the show is collaborative. We made sure that the work that we're showing on a shared screen relates to each other and speaks to each other in some way. That happens through a process oriented around 3D scanning and bringing real-world objects into digital representation. It also happens because of the themes that we're both working on, which include anthropogenic change in the landscape and problematizing between the natural and the human.

CC: Dev was really great at spinning up a document and even tossing in some readings. We were exchanging links back and forth on a conceptual basis that we have both been looking at. Each other's ideas inspired and fostered each other. Even though we weren't directly in constant communication about the works we were making, we both understood and took into account what it meant for our work to be in dialogue. So that was definitely on my mind when I was developing and exploring this body of work.

AM: Would you like to share your reading list?

DH: (laughs) It’s a work in progress, but some names that come to mind are authors like Timothy Morton, Bruno Latour or Ursula Le Guin. I was recently reading THE ENDS OF THE WORLD by Castro and Danowski. They take a leap from Bruno Latour’s FACING GAIA, to talk about how there are many formulations of the end of the world, per se, and how perhaps all of them can be implicated in a sort of anthropogenic thinking about what constitutes world and what constitutes human societies as separate from world.

There's another essay that I didn't share yet, Chris (sorry!), by historian John Tully about the development of the first transatlantic telegraph and how it was deeply entangled with the harvesting of a specific tree resin from Southeast Asia that was used to insulate telegraph cables, which made underwater cabling possible. And it's very interesting, of course, because this is the dawn of the information age, right, the beginning of global telecommunications, yet it was totally dependent on a material from a species of tree, confined to a very specific geographic region, which, sadly, due to colonial exploitation, was totally decimated within 50 years of the invention of the telegraph. So I think there are examples of the sorts of entanglements between nature and technology and the way we use them that persist and are replicated in our present moment.

CC: Part of my master's thesis work was on the social creation of nature, the idea that we invented "nature" as a thing separate from ourselves. Nature is a construct that we can't actually escape being part of. By setting it aside and designating "us" versus a "natural world," it allows us to exploit the thing and keep ourselves separate from it. This is a constant pattern where humans "other" something or someone else so that you can treat it or them differently and separately from yourself. Then it's okay to degrade it, dig it out of the ground, and leave it barren.

I was really affected by Neil Evernden’s SOCIAL CREATION OF NATURE and Simon Schama’s LANDSCAPE AND MEMORY, but it's a sort of long-running theme that I think is really critical in my work and that I've always seen in Dev's work as well.

AM: The title of your exhibition is THIN NATURES. Both of you work with 3D scanning and rendering. Chris, you scan the world around you. What’s your idea behind the title?

CC: I give credit to Dev for the title. He put out many great ideas to get us started, and there was something that struck me about the title, THIN NATURES: it works on a number of levels. On one level, it speaks to the results of the 3D scanning process. I have always been fascinated by the way 3D scanning produces nothing but a set of data points and polygons from the dense “real” world. Perceived by computers, polygons are infinitely thin triangles that only have one side, so this idea of scanning nature as a "capture" process actually produces something that's infinitely shallow.

On another level, the title THIN NATURES also speaks to the way that we lay maps over land and sea. We stake claims to determine where we're going to dig into the earth for materials or where we're going to cut down all the trees and build houses. All of that mapping is done through very sparse datasets like GPS, which don't understand anything about the complex ecosystems of a place or the full repercussions of what we're doing. Our understanding of nature is essentially thin at its very core.

DH: The objects represented in my work, and also in Chris’ work, are 3D scans of real things. For me, I am really interested in trying to reference the real—not a subjective representation of things, but their literal and mundane presence. It’s really about letting things in the real world make themselves present. I like when the liminal digital space can be punctuated and grounded by straightforward objects and artifacts that lend context and narrative.

I am also often working with geological material to build this narrative. Scans of rocks and boulders have come from trips or expeditions to the desert or to derelict mining sites, where I'm capturing elements of the landscape. Geology shows up in my work in a way that connects to the idea of deep time, meaning the geological time scales of mountain buildings and plate tectonics. The current anthropogenic crisis is caused by the inability of humans to think over longer timescales. Geology allows us to think and scale up hundreds of thousands to millions of years, over ice ages or mass extinction events. Juxtaposing these deep timescales with the very present, for instance, the technological artifacts of the last three decades, helps us put humanity’s predicament in context.

AM: How do you approach, for example, scanning a mountain?

CC: I captured this landscape as part of an expedition for some people who were doing a documentary, using real-time 3D environments to tell stories. They were interested in capturing some of the biome of southern Colorado, and I went out to try and do some of that work for them. This involved flying a drone back and forth over this hillside just outside of town, taking hundreds and hundreds of pictures in this semi-methodical process. All those images get turned into a 3D model using photogrammetry. In some ways, I scanned a completely innocuous hillside in the middle of nowhere. But at the same time, it's part of a community that is dealing with having been farmland, but with climate change and drought, it's now being looked at for future mining prospects.

I don't know if you know this, but in America, you may own your house, but somebody else owns all the mineral rights to everything below your house. There's this crazy notion of ownership that we have where our property lines somehow project up into the sky and down into the earth, but actually, what we “own” is quite shallow. So these different maps of ownership at different strata of the geological space are super curious to me. In some ways, that's what I wanted to try and explore in this show.

For one of the animations, I was particularly interested in ground-penetrating radar, and thus the piece is subtitled PENETRATING. I've been watching a lot of these terrible reality TV shows where people are hunting for gold and hunting for resources and other treasures below ground. Watching these people wave wands and use special drones and all this sort of stuff, scanning back and forth over the landscape, trying to divine what's below the surface. And they're all complete crap. In a way, there's something beautiful about the way that the surface ends up hiding what's underneath. But we keep trying anyway. So in some ways, I wanted to capture the attempted violence of that looking process, which can produce treasures for some but complete destruction of ecosystems for others.

AM: During our interview, Chris, you've said that the digital is as ephemeral as flowers. What are your thoughts on the ephemeral nature of the digital?

CC: Increasingly, we're all constantly taking more photos and videos of everything around us. And it's also all being constantly lost. We are uploading all this into the clouds and hoping that platforms will keep it around forever, not remembering that MySpace lost 50 million songs when it collapsed. Every time we switch phones, fragments of our memories are lost as we fail to hit the right buttons and transfer them to the next device. There was something really profound in James Bridle’s book, NEW DARK AGE. The book suggests that our era of digital-based knowledge could be erased by a single solar flare. So, despite the digital realm claiming to be a type of preservation, it is more like a collection of magnetic specks on spinning discs in warehouses in the middle of nowhere that are not going to last in the long term.

DH: In response to Chris I think there are two sides to technology. On the one hand, there's the ephemerality of the digital files themselves; the information, as you mentioned, is stored inside drives or magnetic storage devices. On the other hand, there is a non-ephemeral dimension to technology, which is the physical hardware itself. Computers, phones, devices, servers, and routers are all manufactured with metals, minerals, and materials extracted from the earth. Often, these materials are combined in ways that produce toxic chemicals that subsequently return to the earth. And from a long-term geological perspective, this waste ends up becoming a whole strata within the geosystem infused with technological refuse.

What’s interesting to me is imagining the appearance of these shiny, expensive objects purchased today after being buried under mountains of sand and rock for a few thousand years. And then who might discover these objects in the future, and what might they think about our society based on these artifacts? I think you can tell a lot about a culture and its values from the artifacts they leave behind.

As a side note, Chris, to go back to the ephemerality of digital media, despite this, I have been able to successfully recover files that I burned on DVDs back in 2002 and even from floppy disks from the 1990s! But, of course, all this is very fragile; the information itself is very fragile. Again, I think a big part of my work is to look at the physical artifacts of technology, which are not ephemeral at all. They stick around for a very long time.

CC: I've been going through all my late 1990s and early 2000s-era DVDRs and CDRs. And all the data is decaying, with half of it now completely unplayable. So just 20 years in, our supposedly “stable” storage is already dying. However, the plastic CDR that has some random file name written on it with a Sharpie is probably going to be around for another 6,000 years. And perhaps that same piece of plastic actually holds more significance over time than the original data stored on it. I think about shards of pottery as representing entire cultures that we found 3000 years ago. What kind of shards will be discovered in our future?

AM: What do you think the future will hold? When I was at my parents' home last Christmas, I went through old belongings and found my old Walkman, MP3 player, first iPhone, and iPad (I don't know why I kept all of them), as well as some types of video game devices that I don’t remember having or playing, but I kept them.

CC: Yes! The message etched onto the back of my first iPod is probably going to have more cultural meaning in 200 years than what might have been on the iPod at one point in time. Which is crazy.

AM: And what kind of digital art do you think will stay and have a lasting impact?

CC: I have the privilege of being an artist, a teacher, and a collector. So I interact with art constantly, and I go see art everywhere I travel. So, I'm looking for art that moves me and speaks to me. Art that I'm thinking about a week later, that I'm thinking about a month later. Art that I want to talk to somebody about a year later. There are really amazing ways that art can have an ongoing impact when it's done right.

All of that said, I think it's really difficult in this digital space and the commodified arts space to think about how you balance the "spectacle," which draws people in, and then the "conceptual," which will leave them curious and/or inspired even after they walk away from the artwork. It's a long-term game that we're playing as artists, attempting to speak to people on multiple levels.

AM: Do you make a difference between the criteria for good physical and digital art?

CC: I adhere to the idea that your medium is part of the message. If you're using digital technology to express something, you can't just ignore the fact that you've used this technology or that you've chosen this tool. The tool is part of what you're talking about because you are speaking through it.

I think that in a world that's increasingly digital, we have a huge responsibility as people who are leveraging digital technologies to make art. And there's also a lot of space to manoeuvre, think about, and push technologies. Because, as we all know, there's a lot of money being poured into specific technologies and specific technological paths. If we're going to play in those spaces at the edge of advancing technology, we need to be thinking really critically about what those tools are doing, who they're empowering, and who they're keeping "outside." It's a constant and critical dialogue that I think we have a special responsibility for.

DH: I think working with technology as a medium is a lot more problematic than, say, painting or stone carving, where the materials are, to some degree, more neutral. When you're using a computer, a piece of software, a phone, or whatever, it's all really loaded because that device comes with a lot of other associations and baggage. Who manufactured it? Who benefits from the technology? Who does it harm? What kinds of ecological impacts does it have in terms of its material construction? I think artists who work with technology need to be honest about the technological material being used, what they're doing with it, and acknowledge or respond to those problematic aspects.

Digital art should also not be subject to some kind of exceptionalism. To respond to the question, "What do I think makes good digital art?" I would say that it is the same things that make any good art. There is a tendency to isolate digital artists from other types of practices, and I really try to push back against that and say that digital art should come with the same value judgements as painting, sculpture, or anything else in terms of what the work is supposed to be doing, meaning a way of looking at the world and as a mode of inquiry, as a way of asking questions about the world. And if you're doing that successfully, it shouldn't matter whether it's a painting, a screen, or a pile of bricks on the floor.

To facilitate that in my work, I feel what really works for me is being at that intersection between the digital and the physical, for instance, bringing digital projections into play with physical sculptures or producing sculptures that are digitally fabricated. This interplay between physical and ephemeral is where I can really kind of have a rich interplay between different modes, materials, and dialogues.

AM: What are your predictions for the future of NFTs and digital art?

DH: Looking into a crystal ball is never easy! I think it's difficult for me to answer because I've been working with digital art or technology as part of my art practice for over 20 years, but I was very skeptical about NFTs for quite some time.

So how do I predict the future of NFT's playing out? It seems that, with the cooling effect of the decline in crypto markets, there's also been a better signal-to-noise ratio, and I’m starting to see more serious voices emerge, and I think that's cool. I hope it becomes less about the market, less about who's selling for what prices on what platforms or whatever, and more about what people are actually doing, what people are saying with their work, and really being able to hear more interesting voices. And I do think that it’s an amazing time for digital art, cryptomarket aside, given that previously there was never a viable market for video work, for doing generative animation, or for these sorts of things that are very ephemeral. Digital work never lends itself to the cash-and-carry model that traditional galleries favor. And so for the first time to be able to easily sell video pieces this way, there is potential there that certainly did not exist before, and certainly, I hope, is going to become a much more stable way for people who want to have a viable art career doing digital work.

CC: I'm also quite excited for things to calm down. We need time for long work. We need time for complex work. I think the market really drove a lot of artists to speed up their practice, and so it was difficult for those who spend weeks, months, or even years on complex work.

I'm really excited that we have this framework for supporting digital artists that can exist. I think artists are going to continue to find ways to create new marketplaces using NFTs, and there's a set of tools now that enable long-term relationships that I'm really quite excited about, both as an artist and collector.

It's exciting that we can slow down and make work that speaks to even deeper things. This is not to suggest that those artists who make work every day are somehow not making great art. I love the fact that some people can also make a living by creating art every day. But over the last couple of years, it felt like everybody needed to be doing that in order to keep collectors' attention, and that was all just too much. I'm also really excited for the ongoing technological changes and what is becoming possible. I'm particularly excited to be done with things like rendering, which seems more and more archaic to me these days. So I'm interested in real-time tools and creative coding. I'm still not using AI tools at all, but I'm really interested in what some of those tools are enabling for my students and other emerging artists. So it's a really exciting moment to see and teach digital arts.

AM: Thank you for your time and thoughts, Chris and Dev!